Why Teach Chinese through Song

By Hong Zhang

"Language is a perpetual Orphic song."-Percy Bysshe Shelley (note 1). "Song intones language 歌咏言"-The Book of History(Shangshu 尚书)(note 2). These quotations, one from a Romantic English poet, one from a Confucian classic, indicate that language and song, speech and music are aspects of a single act.

That act is communication.

Affinities between language and song have been explored by musicologists and voice teachers, but have drawn scant attention from linguists and language teachers. As an experienced Chinese language teacher and professional singer, I intend to correct that oversight by promoting the study of spoken Chinese through the study of Chinese song.

Song is the highest form of speech. It is nothing more than the elongation of vowels and the extension of pitch inflections found in everyday conversation. As sung language, a good song synthesizes the linguistic, poetic and musical beauty of speech. Because song “ups the ante” by emphasizing the color, pronunciation and intonation of every syllable, it is a valuable tool for improving students’ spoken language skills.

The success of this approach has been demonstrated in the course “Singing Chinese,” which I developed at Binghamton University. This is a specially designed, interdisciplinary course, emphasizing both language acquisition and music appreciation and performance. The songs in my textbook are art songs, folk songs, and popular songs from the Mainland, Taiwan, and Hong Kong. Song lyrics serve as the main texts, accompanied by vocabulary lists and exercises. Students learn new words and sentence patterns as in regular language classes, while the improvement of pronunciation, diction, voice projection, and language expression are achieved through singing practice. Students go through a step-by-step learning progression, from “singing along” to “singing alone.” By semester’s end, although students are not expected to sing solo professionally, they will be able to sing with choral expertise and to actually please crowds at Karaoke sessions.

The remainder of this article focuses on four pedagogical issues.

I DICTION

A singer does not merely give voice to signs set down on paper; he must have clear diction and a good accent as well. People usually pay greater attention to these issues when singing their native language than when speaking it. It comes as no surprise, then, that singing a foreign language helps students to focus more on phrasing and enunciation than they do during grammar exercises, which usually stresses memory skills and mastery of sentence patterns over articulation.

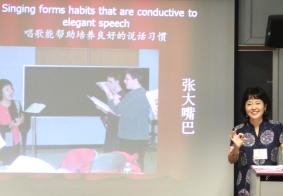

1. Singing forms habits that are conducive to elegant speech. Many students at the elementary and intermediate levels do not open their mouths widely enough when speaking Chinese which results in mumbled speech. When singing however, students must open their mouths in order to project and to produce a pleasing tone for each syllable. Once acquired, this habit carries over into everyday speech.

2. Singing increases sensitivity to tone. The four tones of spoken Chinese pose an intimidating obstacle to most foreign learners of the language. The ability to recognize and reproduce various pitches, can be enhanced by musical training. A singer is said to sing more with the ear than with the mouth. In learning to sing, we learn to listen.

3. Singing improves the accuracy of spoken vowel sounds. In order to project effectively, singers must sustain clear vowel sounds through the duration of each note. Because vowels have a shorter duration in speech than in song, students who practice singing a vowel will find it relatively easy to speak it accurately.

4. Singing gives students greater command of the organs of speech. When speaking a foreign language, most people unconsciously tighten their mouths and throats. To produce a mellifluous natural sound, a singer must relax her jaw, tongue, lips, and neck. Through singing, students develop habits of relaxation which are easily transferred to spoken exercises.

5. Singing improves enunciation. It can be hard to understand a lyric, even in one’s native language. This is because in song words are presented with artifice; the composer dictates the pitch and duration of notes. To communicate effectively despite rhythmic and harmonic constrictions, a singer must pay constant attention to phrasing to maintain the basic linguistic shape of an utterance. This training teaches skills needed for clear and natural speech.

6. Singing enables students to recognize their own verbal idiosynchrasies. The long duration of sung syllables exposes and exaggerates errors that may go uncorrected in spoken drills. Many students who speak rapidly and with grammatical accuracy in the classroom use their mnemonic skill and nimble tongues to mask sloppy speech. When singing, there is no place to hide.

II EXPRESSION

Students are often shy when speaking Chinese in front of others. In group discussions, they avoid eye contact and may speak in a monotone. The emotional color that is an intrinsic part of music helps students of “Chinese through Song” overcome these problems. The joyful naiveté of folk songs, the romance of art songs, the sentimentality of popular ballads, and the brash pronouncements of rock and roll demand that singers check their reticence at the classroom door. This course is not designed to turn students into professional singers. What it can do is invigorate their spoken Chinese in a way that facilitates communication with Chinese audiences and interlocutors.

III FLUENCY

The charm of singing lies in legato, the smooth transition from one note to another that depends upon the composers’ treatment of lines, phrase groups, harmonic progressions and so on. An appreciation for the mechanisms of legato will help students avoid choppy speech and achieve greater fluency.

IV MEMORIZATION

Rhyme, rhythm, metaphor, and other poetic devices make most poems more memorable than ordinary speech. When music is combined with poetry, the result is often unforgettable. Repetition, a basic structural feature of music and poetry, is also a great aid to memory. It guides recognition of grammatical structures, phrases, and collocations. The mnemonic qualities of song guarantee that the lyrics will be inscribed in the student’s mind long after written texts and pattern drills are forgotten.

Note1. Prometheus Unbound, act 4, line 415.

Note2. Shangshu, an anthology of early historical documents, is said to have been compiled by Confucius 孔子(551-479 BC). This quotation is from Sun Xingyan 孙星衍 (1753-1818) .ed., Shangshu jinguwen zhushu 尚书今古文注疏 ,2vols. (Beijing: Zhonghua, 1974), 1.1.70.

Hong Zhang holds a Master of Music degree in Voice Performance from Binghamton University, SUNY, and a Bachelor of Music degree in Voice Performance from the University of Wisconsin-Madison. She is the founder and director of Song of Silk, a performance group that aims to bridge East and West. Zhang has been an active soloist in many concerts and groups, including the Shanghai Philharmonic Society, the Milwaukee Symphony Chorus, the Milwaukee Chamber Orchestra, the Symphony Orchestra of the University of Wisconsin-Madison and Eastern Silk. In addition, Zhang gives lectures, recitals and workshops on Chinese vocal music and culture nationwide. Currently a Senior Instructor of Chinese at Binghamton University, Zhang’s curriculum includes the ground-breaking course, Singing Chinese. She has also co-authored Chinese through Song and Cultural Chinese: Readings in Art, literature, and history.